Twombly & Rauschenberg

Cy Twombly and Rauschenberg, Rome, 1961 Photo: Mario Schifano, © 2013 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/SIAE, Rome

Cy Twombly and Robert Rauschenberg inspired each other throughout their lives. Two exhibitions – Twombly at the Centre Pompidou in Paris and Rauschenberg at Tate Modern in London – celebrate this artistic and personal intersection. The two shows are the first full-scale retrospectives since their deaths in 2008 and 2011 respectively.

CORONATION OF SESOSTRIS, PANEL 5, 2000. / (Pinault collection) Photograph© Cy Twombly Foundation

CORONATION OF SESOSTRIS, PANEL 6, 2000. / (Pinault collection) Photograph© Cy Twombly Foundation

Although Twombly and Rauschenberg never collaborated to produce shared works, their histories were intertwined. They first met in 1950 as college students, immediately becoming friends and then lovers. Two years later, Twombly, a promising young artist, won a grant, which he used to travel to Europe and North Africa, inviting Rauschenberg to join him on the trip. For both men this voyage became much more than just a source of inspiration; it was a turning point in their lives and artistic careers.

BED, 1955, Combine; The Museum of Modern Art, New York Gift of Leo Castelli in honor of Alfred H. Barr Jr. © 2017 Robert Rauschenberg Foundation.

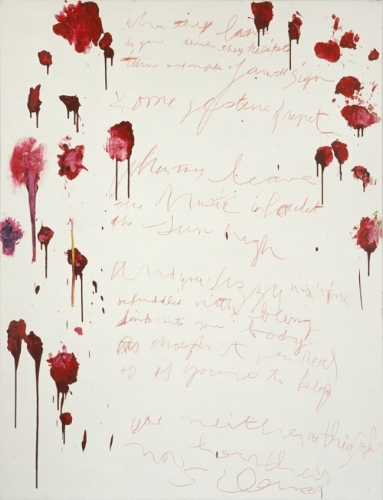

Cy Twombly’s retrospective at the Centre Pompidou opens with Africa-inspired paintings, in which he used his signature technique for the first time: indecipherable writing, deliberately primitive and gestural. During his travels to Italy and Morocco Twombly was inspired by excavations of Roman cities, which awoke in him a deep fascination with antiquity. Italy was the first European country he visited and he was so overwhelmed by its immortal grandness that he moved to Rome in 1959. He stayed in Italy for the rest of his life. The sense of immortal grandness is expressed in works such as "Nine Discourses on Commodus" (1963), "Fifty Days at Iliam" (1978) and "Coronation of Sensostris" (2000). Twombly experimented constantly throughout his career, creating monochrome sculptural pieces, adopting minimalism in response to pervading trends. In later life, he turned back to bright, colourful canvases.

UNTITLED, (PEONY BLOSSOM PAINTINGS), 2007. / Photograph© Cy Twombly Foundation

The contrast with Rauschenberg's works is surprisingly stark. Unlike Twombly, he spent all his live in the USA and his art responded to contemporary political realities, rather than to the country’s history and heritage. He developed his style by constantly seeking new materials and forms of expression. During the same trip to Italy and Morocco with Cy Twombly, he created intricate collages and assemblages that would later be reinterpreted in his famous Combines – paintings made of everyday materials. "Bed" (1955), for example, is formed of a painted pillow and blanket (the artist could not afford a new canvas), which were hung on the wall like a traditional painting. Rauschenberg then experimented with abstract expressionism and pop art, adopting the silkscreen technique employed by Andy Warhol. He also tried his hand as a choreographer, as well as collaborating with engineers to create "Mad Muse" (1968-1971), a large metal tank full of bubbling bentonite clay – the first-ever live monochrome painting.

MIRTHDAY MAN [ANAGRAM (A PUN)], 1997, Collection Faurschou Foundation, © 2017 Robert Rauschenberg Foundation.

Twombly and Rauschenberg, two artists who began by working alongside each other, moved in different directions for much of their lives but finally reached common ground towards the end of their 60-year careers. Decades of antique history, political references and sophisticated poetic quotations, all of it wrapped up by simple peonies. It is suitably symbolic of this artistic union at the end of their lives that the Rauschenberg retrospective also ends up with bright expansive collages, focused on visual effect rather than political subtext.

This article was written by Maria Averina, an art historian.

![MIRTHDAY MAN [ANAGRAM (A PUN)], 1997, Collection Faurschou Foundation, © 2017 Robert Rauschenberg Foundation.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57dfd21e8419c2abeec60e26/1488412581404-6FBVCPZBPH2DJJFP6N0I/image-asset.jpeg)